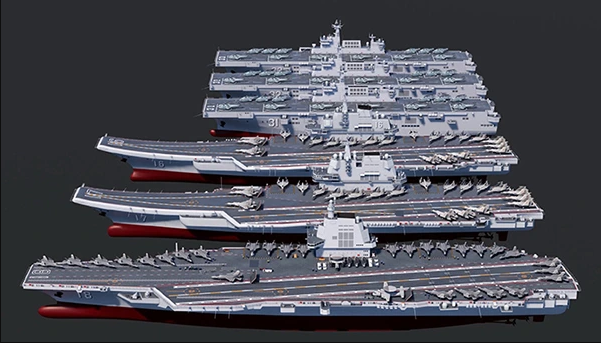

China’s Growing Aircraft Carrier Fleet — Status in 2025 and Where the PLAN Is Heading Next

China is rapidly expanding its aircraft force: in addition to its two operational carriers, the Liaoning and Shandong, a third, the modern Fujian, has undergone intensive trials in recent months. The pace of construction and the technological leap towards electric catapults are changing the balance of power in the Indo-Pacific, while the new platforms still face operational and logistical constraints.

The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is entering a new phase in which aircraft carriers are no longer a symbolic project but a real operational capability. After a decade of rapid construction, the PLAN has two operational carriers — the Liaoning and the Shandong — and a third, the Fujian (Type-003), is in the final sea trials phase. This technological shift, in particular the transition from the classic jump-launch of aircraft to electromagnetic catapults, allows for the deployment of more modern aircraft, an increase in the number of operations, and greater operational flexibility. However, even with this development, there are significant limitations, whether in the area of logistics, escort ship support, or crew experience. The article provides an overview of the current state of China’s aircraft carrier fleet, technological innovations, industrial background, and impacts on regional strategy.

Current inventory and status: what is operational and what is testing

As of 2025, the Chinese People’s Navy has two fully operational aircraft carriers and one carrier that is in the final testing phase.

Liaoning (Type-001) was China’s first aircraft carrier, originally a reconstruction of the Ukrainian vessel Varyag. It entered service in 2012 and is primarily used for training deck crews and testing deployment tactics. Liaoning has a tonnage of around 60,000 tons, uses a classic “ski-jump” system for aircraft takeoff and can accommodate approximately 40 aircraft, mostly J-15 fighters and several helicopters. Despite its limited operational flexibility, the Liaoning serves as a foundation for building the PLAN’s carrier operations know-how.

The Shandong (Type-002) entered service in 2019 and is the first fully Chinese carrier design, based on the Liaoning experience. It is larger (about 70,000 tons) and also uses a “ski-jump” system, but has an improved deck structure and the ability to accommodate over 40 aircraft. The Shandong is now the PLAN’s main operational carrier, capable of longer missions and a wider range of air operations, including deployments on the high seas and support for blockade or deterrence missions.

The Fujian (Type-003) is the newest carrier, currently in the final stages of sea trials and is expected to enter service in 2025–2026. Fujian represents a technological leap forward over its predecessors: it has a tonnage of around 80,000 tons and, for the first time on a Chinese carrier, is equipped with electromagnetic catapults (EMALS-like), which allows the launch of heavier and more modern aircraft, including the planned deployment of J-35 fighters. It is assumed that Fujian will be able to accommodate over 50 aircraft and increase the operational flexibility of the PLAN, while its introduction marks China’s transition from a learning fleet to a real projection force in the Indo-Pacific.

Type 075 (LHD) represents a new category of large amphibious helicopter carriers, which are functionally close to light aircraft carriers. With a displacement of around 35-40 thousand tons and a capacity of up to 28 helicopters of various types (transport, attack, anti-submarine), they provide the capability for large-scale amphibious operations. Type 075-class ships have a landing craft dock (LCAC) and spaces for transporting marines and heavy equipment. By 2025, the PLAN will have at least three units of this class in service, which can operate both in airborne operations and as a support air platform during blockades or crisis deployments in the South China Sea.

The Type 076 (planned class) represents an even more ambitious concept – a hybrid between an amphibious ship and a light aircraft carrier. According to available information, it is to be equipped with electromagnetic catapults and a modified deck runway, which would allow the launch of not only helicopters, but also airborne drones and lighter aircraft. The Type 076 could thus function as a test platform for the integration of unmanned aerial systems into the PLAN’s operational doctrine. Its role could be to support amphibious assaults, deploy drone swarms, or expand aerial reconnaissance and electronic warfare on smaller carrier vessels. The projected tonnage is estimated at 50,000 tons.

In addition to these three heavy and two lighter classes, other units are under construction or planning, including the Type-004 concept, a potentially nuclear-powered carrier that could form the basis of a future multi-carrier fleet. The pace of construction and the scale of investment indicate the PLAN’s ambition to rapidly increase its operational range and power projection capabilities in the region.

Technology and Platforms: What’s Changed

The evolution of China’s aircraft carriers over the past decade reflects rapid technological advances that have taken the PLAN from a learning fleet concept to a real operational force projection capability. A key change is the shift from the traditional “ski-jump” takeoff to electromagnetic catapults on the Fujian (Type-003), which allows the launch of heavier and more modern aircraft with full combat loads. In addition, electromagnetic catapults allow for a higher frequency of launches, which increases the operational tempo and flexibility of the carrier in combat scenarios. The carrier’s air power is also changing. While the Liaoning and Shandong mainly use J-15 fighters, the Fujian is designed to integrate the new generation of J-35 fighters and to test carrier-launched unmanned aircraft. These platforms expand the PLAN’s capabilities in the areas of reconnaissance, electronic warfare, and precision strikes on targets far from China’s shores. Combined with modern anti-submarine warfare (ASW) helicopters and supply aircraft, this creates a much more versatile and operationally capable air potential.

Another key element is the modernization of the onboard systems: Fujian has an improved radar and electronic sensor, a sophisticated air traffic control system, and the integration of data from the escort fleet. This allows for more effective coordination of air operations, including the simultaneous operation of multiple aircraft types. The planned integration of the nuclear-powered Type-004 could further extend the fleet’s operational range and reduce dependence on logistical supply chains, a key factor for long-term operations in the Pacific Ocean. Overall, the technologies and platforms of China’s aircraft carriers combine proven concepts (ski-jump) with modern innovations (EMALS, new fighters, and drones), giving the PLAN a significantly broader operational palette and the ability to gradually develop the tactics of a truly projective naval force.

Industrial background and construction pace

The development of Chinese aircraft carriers is closely linked to the capacities of the Chinese shipbuilding industry, which has undergone significant modernization and expansion. The main construction of carriers is taking place in shipyards in Shanghai (Jiangnan Shipyard) and Dalian, each of which has modern dry docks, assembly halls and technologies for the construction of large steel blocks. This infrastructure allows China to maintain a relatively high construction pace, which is reflected not only in the rapid completion of Liaoning and Shandong, but also in the current work on Type-004.

The construction pace indicates the PLAN’s ambition to build a multi-carrier fleet in the next decade. Expert estimates indicate that China could have four to five aircraft carriers by 2030, with each subsequent type being technologically more advanced than the previous one. This trend is also accompanied by the development of supporting infrastructure: ports for carrier docking, supply and repair capacities, which are key to their long-term operational capability. It is also significant that China is simultaneously developing and testing new aircraft platforms, including drones and heavy fighters, to fully utilize carriers with catapult systems. Such coordination between the shipyard, aircraft production and crew training allows the PLAN to rapidly increase the operational readiness of the fleet and gradually increase the scope of its power projection in the Pacific Ocean.

Operational doctrine and tactics

The growing Chinese aircraft carrier fleet is closely linked to the changing operational doctrine of the PLAN. In the past, Chinese carriers served mainly for training deck crews and testing tactics, but now they are beginning to fulfill real operational roles, especially in the areas of power projection and deterrence. The deployment plan focuses on the Indo-Pacific, especially around Taiwan, the South China Sea and the East China Sea, where aircraft carriers can support naval blockades, reconnaissance operations or possible rapid deployment of air power.

Current tests and exercises show that the PLAN is trying to develop twin-carrier operations tactics, i.e. the deployment of two carriers in the same area, which allows for continuous air presence and increased flexibility. Such an approach imitates the US Navy models, but is currently limited by the operational experience of the crews and logistical capabilities. Support for escort ships (destroyer, destroyers and frigates) and anti-aircraft defense is key to keeping the carrier in the combat area, which is why the PLAN is also developing an escort fleet. An important element of the doctrine is also the integration of new types of aircraft and unmanned systems that allow reconnaissance, electronic warfare and precision strikes on targets hundreds of kilometers from the Chinese coast. The planned combination of carriers with these assets gives China the ability to operate at greater distances and with greater flexibility, although there are still limits in the areas of ASW, logistics, and the complex command of multiple carriers at once.

Limitations and Weaknesses

Although China’s aircraft carrier fleet is growing rapidly, there are still significant limitations that limit its actual operational power. The first factor is logistics and supply: aircraft carriers require constant support from escort ships, fuel, ammunition, and supplies. The limited capacity of supply vessels and the limited experience of the crews continue to reduce the operational time and range of the carriers, especially during long-term missions far from home ports. Another limitation is anti-submarine warfare (ASW). The Chinese fleet still lacks a fully integrated ASW network that can effectively protect the carriers from the modern submarines of potential adversaries. Although new helicopters and unmanned anti-submarine warfare systems are planned, their deployment and interoperability with the carriers are still in the early stages.

The third area of weakness is operational experience and crew training. While the technical specifications of the carriers allow for high flexibility, the actual ability to conduct complex operations, such as twin-carrier deployments or coordinated actions with international fleets, is limited. The history of the Liaoning and Shandong deployments shows that the PLAN is still learning to optimize tactics, command and control of air operations, a factor that significantly affects the effective combat power of carriers. Overall, it can be said that China’s carrier fleet poses a growing threat on a regional scale, but its operational capabilities are currently limited by a combination of logistical, technical and human factors. These weaknesses define the current reality of China’s power projection and set the limits for the immediate use of carriers in complex combat scenarios.

Regional and strategic implications

The growth of China’s aircraft carrier fleet has a significant impact on the security balance in the Indo-Pacific. For Taiwan, Chinese carriers pose a real threat because they allow the PLAN to rapidly project air power over the Taiwan Straits, complicating the defense planning of the Taiwanese military and deterring potential third-party interventions.

For Japan and other states in the region, including the Philippines and Vietnam, Chinese carriers represent an increased need to modernize naval forces and anti-submarine capabilities. Regional alliances, including the US Navy and partners in the Indo-Pacific, must adapt to the PLAN’s growing operational reach and develop protocols for monitoring and potential deterrence operations. The simultaneous deployment of two carriers in the Pacific Ocean region already signals a shift towards real force projection, not just a symbolic presence.

Strategically, the development of Chinese carriers also has an impact on the planning of the US and its allies. The increasing number and technological level of PLAN carriers requires a review of operational scenarios, exercises, and logistics chain planning to maintain the ability to respond effectively to potential crises. This process is also forcing regional actors to reassess investments in anti-aircraft systems, anti-submarine capabilities, and the ability to rapidly deploy their own air and naval forces.

Martin Scholz