Andrei Fursov: How the USSR created a Western paradise and globalization buried it

Russia, May 18, 2025 – “Middle class”. This term has acquired an almost magical meaning in the post-Soviet period and acts as a “carrot” to sweeten the shocking blows of the reform whip. This is the bright future that political technologists and ideologists of the brave new post-communist world promise Russians. It was suggested that the majority of the population would join the ranks of the middle class; even publications are appearing – from stellar to those that declare themselves analytical – that “position themselves” as publications for and on behalf of the Russian middle class. However, it turns out that this class is almost invisible, despite the joyful statistics of salaries and consumption.

Of course, in every society there is a middle, defined by the law of averages, but not every middle is a middle class. And what could have become the middle class in the Russian Federation, has actually been reduced (killed) twice already – in 1992 and 1998. But we are still very often presented with the West as a middle-class paradise. Is that so?

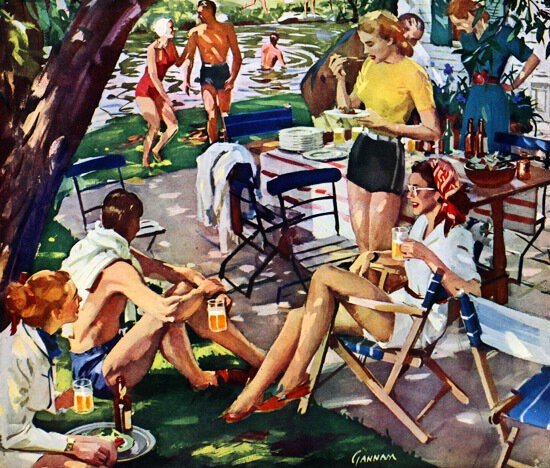

The core of the capitalist system was the middle class, which began to take shape in the second half of the 19th century. However, the first century of its existence can hardly be called happy: the “social pie” was relatively small, and capitalism was quite brutal. The life of the average middle-class person was a struggle with his peers to keep him from sliding down, and with those who pushed from below to block his way up, because social life is a zero-sum game. The fascist revolution in Italy and the National Socialist revolution in Germany illustrate how the middle classes can fight for their position when faced with the threat of proletarianization. Gradually, the position of the Western middle classes improved, but very gradually. A qualitative change occurred after the second World War, from 1945 to 1975. The French call this period “les trentes glorieuses” – “the glorious thirties” – and indeed it was, not only in France, but also in other Western countries.

The post-war thirties were the triumph of the middle class and the so-called welfare state (a more accurate translation: “universal welfare state”). The main reasons for this triumph are two – economic and political. The post-war thirties coincided with the “upward wave” of the Kondratiev cycle, i.e. the rise, growth of the world economy from 1945 to 1968 – 1973. However, this “upward wave” fantastically surpassed all previous periods of growth and expansion of the world economy (1780 – 1815, 1848 – 1873, 1896 – 1920). The “glorious thirties” showed unprecedented results: during this period, the same amount of goods and services was produced as in the previous 150 years.

One of the reasons was, of course, the colossal destruction of the Second World War. The significantly increased “social pie” in the post-war West provided the elite of Western countries and the entire capitalist system with a “fund” from which it was theoretically possible to give something to the middle class, thereby increasing its well-being, and this was for economic reasons: well-being increases demand, and thereby stimulates economic development. However, capitalism is not a philanthropic organization and will not provide well-being to anyone, especially not to such a relatively massive layer as the middle class. The “iron heel” had to soften and significantly improve the situation of the middle (and part of the working) class, it was forced to do this by certain circumstances, and these circumstances were outside capitalism. We are talking about the presence in the world of systemic capitalism of the socialist camp.

The very existence of the USSR, its rapid economic development, which even Western politicians in the second half of the In the 1950s and 1960s, the impression that the USSR would overtake the USA, its egalitarian social system, its ability to materially support the anti-capitalist movement throughout the world, including the communist, socialist and workers’ parties in the West itself (that’s Stalin’s: defeat the enemy on its territory), all this forced the bourgeoisie to pacify its working and middle classes, to pay them off. From the working class – so that it would not rebel, from the middle class – so that it would fulfill the function of a social buffer, a buffer between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat.

The means of nourishment and pacification was the welfare state, which, through the tax system, redistributed a part of the financial resources (quite significant in absolute terms) from the bourgeoisie to the middle class and, to a lesser extent, to the working class. As a result, already in the mid-1960s, a numerous and relatively prosperous middle class. Of course, the bourgeoisie did not engage the redistribution mechanism out of good will. The welfare state is a clear deviation from the logic of development and the nature of capitalism, which can only be explained to a small extent by the interest in creating demand and consumers of mass products. The main point is something else – the presence of systemic anti-capitalism (historical communism) in the form of the USSR.

During the Cold War, the global confrontation of the USSR, in the struggle between two global projects, the bourgeoisie had to buy off the middle and working classes, pacify them (capital taxes, high wages, pensions, allowances, etc.). The very existence of the USSR, an anti-capitalist system, thus forced the capitalist system at its core to break the class, capitalist logic, to dress in quasi-socialist garb. In the mid-1960s, the Western middle class not only gained economic power, but also became a serious political force, materializing in left and center-left parties, which also worried the establishment. The beginning of the 1970s was in many ways a turning point.

First, the “downward wave” of the Kondratiev cycle was launched, a world economic recession began, and quickly and sharply – in the USA. On August 15, 1971 (for the first time since 1894), the US recorded a trade deficit, Nixon announced that America was rejecting the Bretton Woods agreements and would stop exchanging the dollar for gold; the next day, all European currency markets closed. In 1973, the US devalued the dollar by 10%. In the same year, the oil crisis began and the world entered a period of prolonged global recession. In 1975-1976, inflation gripped the world. Post-war prosperity ended.

Secondly, at the turn of the 1960s and 1970s, the welfare state with its huge bureaucratic apparatus reached the limit of its administrative and political effectiveness.

Third, and most importantly, the burgeoning middle class had become too great a burden for the capitalist system (even in its relatively prosperous core), and the global economic downturn, together with the inefficiency and costliness of the welfare state, had exacerbated this situation. The size of the middle class, multiplied by the level of its welfare, had grown beyond what the capitalist system could provide without fundamental changes in its nature and without significant further redistribution at the expense of the upper strata. The political aspirations of the middle class posed no less, if not an even greater, threat to it.

In this situation, the masters of the capitalist system stopped retreating, regrouped, and launched a social counteroffensive. The ideological and theoretical justification for this counteroffensive was the extremely important and frankly cynical document “The Crisis of Democracy,” written in 1975 by “three wise men” – S. Huntington, M. Crozier, and Dz. Watanuki – by order of the Trilateral Commission created in 1973 (a “corridor” of a new type, whose task was, as a “good investigator”, to suffocate the USSR in its embrace). However, the weakening of democracy in the interests of the Western elite was not a simple social and political task. Who was the support of Western democracy that needed to be weakened? The middle class and the active upper part of the working class. They were the ones who were hit first.

Market fundamentalists Thatcher and Reagan came to power in Britain in 1979 and in the USA in 1981. They reflected a significant change in the social face of the Iron Heel itself: the “old” bourgeoisie and bureaucracy associated with state-monopoly capitalism were replaced by a young, predatory faction of the corporatocracy, directly linked to transnational corporations, which had been fighting for a place in the sun since the 1940s and 1950s and had finally succeeded (the US defeat in Vietnam contributed in no small measure to this).

The main task of the first president and prime minister from the corporatocracy was to dismantle part of the welfare state and attack the middle and working classes, which Reagan and Thatcher did in the 1980s. However, as long as the USSR existed, it was impossible for the “ring rulers” of the capitalist system to completely reverse such a course. This has two consequences.

The first is the course to sharply weaken the USSR (in 1989-1990 it was replaced by the course to break up and destroy the USSR); for this purpose, the USSR was lured into Afghanistan, which was followed by a new sharp turn of the “Cold War”. The second was an attempt to take from the middle layers of the core and the middle layers of the periphery what could not be taken immediately, and to destroy them as a class. In the 1980s, the IMF’s structural economic reforms in Latin America almost completely destroyed the Latin American middle class; the middle class of the most developed countries of Africa (Nigeria) also suffered. Funds from the expropriation of the peripheral middle classes were pumped to the West, which somewhat slowed down the offensive of the upper classes against the Western middle class.

The collapse of the USSR removed the factor that prevented a full-fledged offensive of the “iron heel” against the core of the middle class – now there is no need to pacify anyone, you can rob on the international stage (Yugoslavia, Iraq) and inside the country. And a wonderful tool appeared – globalization in the American style. However, the first victims of this late capitalist tool were the middle classes of the former socialist countries. If in 1989 in Eastern Europe (including the European part of the USSR) 14 million people lived below the poverty line, in 1996 it was 169 million. The “reforms” let the former socialist middle class go under the knife and became its elementary expropriation. This partially eased the pressure of the “iron heel” on the middle class, but only partially – the bourgeoisie took revenge for decades of forced “social diets” in relation to the masses.

Symbolically, the historical twentieth century began with the book by J. Ortega I. Gasset “The Revolt of the Masses” (1929) and ended with the “Revolt of the Elites” by K. Laš. Globalization has become the most powerful weapon of the upper classes against the lower and middle classes. Scientifically demanding production, unlike industrial production, does not require a significant number of working and middle classes, and therefore, for political but also economic reasons, they can be treated without ceremony – vae victis (Latin for “woe to the vanquished”).

The erosion and stratification of the middle class that is taking place in the West leads to the emergence of a simplified social structure: a wealthy minority, to which the so-called new middle class belongs. This is already reflected in the sociological theory of “20:80”, where 20% are rich, 80% are poor, and there is no middle class. Of course, this is not a reality yet, but a trend, but this trend is obvious, strong and confirmed by statistics even in rich countries like the USA. In 2005, compared to 1975, only 20 percent of Americans saw their incomes increase, while 80 percent saw their incomes decrease. It is clear that in poorer countries this ratio is no longer 20:80, but 10:90 or even 5:95, and the process of disintegration/destruction of the middle class is much faster – the former Soviet middle class was destroyed in 6-7 years.

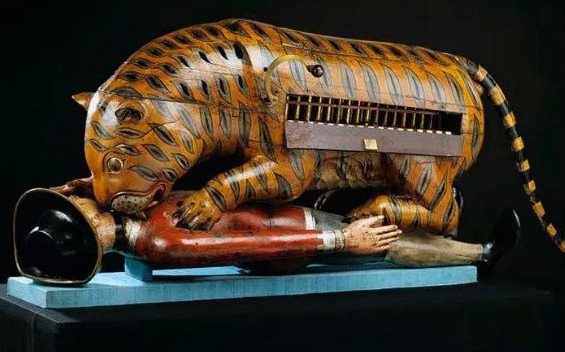

It should be emphasized here that the disintegration of the middle class and the deterioration of its position is a global process characteristic of a late capitalist society that is entering a systemic crisis. The first victims of this crisis are the middle class and the nation-state in the form of a welfare state. From a social point of view, the last 30 years can be globally perceived as a social struggle between the “new bourgeoisie” – the corporatocracy (the French sociologist D. Duclos calls this layer the “hyperbourgeoisie” or “cosmocracy”, emphasizing its parasitic nature and orientation towards draining the surplus product primarily from the middle class) and the middle classes, in which these classes were defeated. The happy life of the middle class in the West turned out to be very short, similar to the life of Francis Macomber, the hero of Hemingway’s short story.

In Russia, the Gorbachev and especially Yeltsin’s government was, among other things, a Russian manifestation of a world struggle in which a part of the nomenklatura in alliance with the criminal class and foreign capital socially defeated the middle class, having previously (and this was the essence of the Gorbachev government) blocked the path of democratization in the interests of the middle class and replaced it with liberalization. Yeltsinism fulfilled the task of economic expropriation. All today’s talk about a bright future for the middle class in our country or in the West is either impenetrable stupidity or a deliberate and cynical lie with quite obvious political goals.

“It was a wonderful time. ” Great music, great cars, great musical equipment, freedom of movement around the world. “And how we “envied all this in the Soviet Union. And what became of them? It’s scary to think about it. There is nothing left but pity for them.” – nizhlogger.

Andrei Fursov