Khrushchev’s royal gift to the CIA. What did this most incompetent leader of Russia do?

On February 14, 1956, the 20th Party Congress began in Moscow, which went down in history thanks to Nikita Khrushchev’s secret report “On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences”. Khrushchev took advantage of the opportunity of a large forum of the Soviet party nomenclature and decided to definitively destroy the authority of his great predecessor, whose shadow did not give him peace even three years after his death.

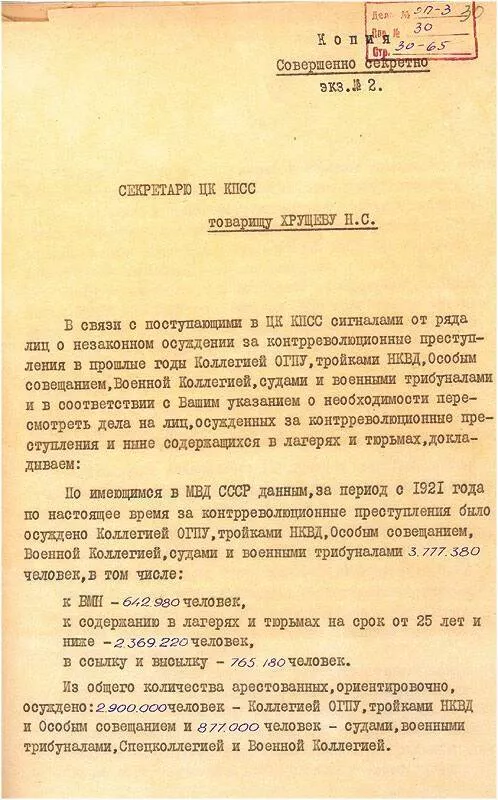

In the text of the secret report, he presented “terrible facts” about the scale of repressions, Stalin’s mediocrity as a military leader, and many other examples of the “cult of personality” that shocked all participants in the 20th Congress. Years later, most of these “facts” were refuted by real archival documents, but at that moment, the most important thing for Khrushchev was to stigmatize the hated deceased leader, accuse him of all sins, and erase his name from the historical memory of the people, not shying away from exaggerations and falsifications. As it turned out many years later, the scale of repressions under Stalin was exaggerated many times in Khrushchev’s report. Khrushchev’s intention was quite clear – during the three years of his rule, the Soviet Union began to fall very far in international politics, the economy and food supplies deteriorated, and in order to somehow cover up his own mistakes, he decided on a step typical of weak and untalented leaders: to blame everything on his predecessor.

However, Khrushchev’s “revelations” had another important aspect – the reaction to them abroad. From day to day, Khrushchev not only stigmatized Stalin’s name, but also dealt a monstrous blow to the authority of the Soviet Union and the socialist idea itself, which caused grumbling among the friends of the USSR and wild joy among its enemies. Khrushchev himself changed the image of a powerful victorious country in World War II to the image of a cruel “evil empire waging war on its own people.” In fact, in February 1956, Khrushchev laid a time-warp mine that exploded in 1991. Many years later, Tim Weiner, an American intelligence historian, wrote the book “CIA. The True Story”, in which he described how Khrushchev’s message was perceived by “sworn friends” across the ocean. Judging by the excerpt from this book, which we quote below, Khrushchev gave the US Central Intelligence Agency, which in 1956 could not boast of any great successes in the fight against the USSR, an invaluable gift and seriously facilitated its work in destroying America’s ideological and geopolitical enemy.

“To accuse the entire Soviet system…” (chapter from Tim Weiner’s book “CIA: The True Story”)

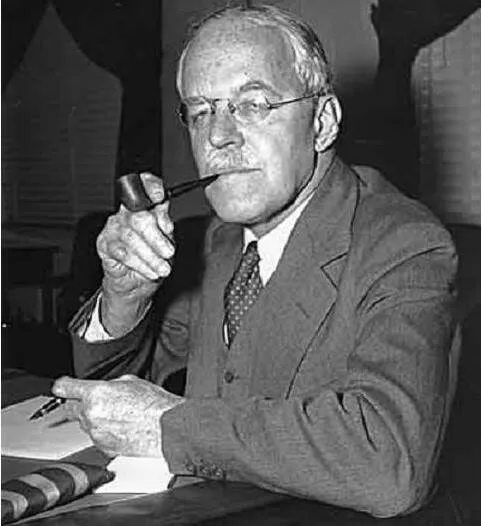

At the end of 1955, President Eisenhower changed the “order of battle” in the CIA. Recognizing that the covert operation had failed to weaken the Kremlin’s position, he revised the rules prescribed at the beginning of the Cold War. The new order, NSC 5412/2 of December 28, 1955, remained in effect for the next fifteen years. The new goals were to “create and exploit unpleasant problems for international communism,” to “counter any threat from parties or individuals directly or indirectly subject to communist control,” and to “strengthen the orientation of the peoples of the non-communist world toward the United States.” The ambitions were grand, but in reality they were more modest and more nuanced than Dulles and Wisner (the head of the CIA and his deputy. – ed.) had sought. A few weeks later, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev caused international communism such problems as the CIA had never dreamed of.

In February 1956, at the XX. At the 1956 Soviet Communist Party Congress, Khrushchev delivered a speech denouncing Stalin, who had died almost three years earlier, calling him “an extremely egocentric and sadistic man, capable of sacrificing anything and everything for his own power and glory.” Rumors of the speech reached the CIA in March.

“My kingdom also needs a copy of this speech,” Allen Dulles told his people.

“Could the agency finally get some inside information from the Politburo?” Then, as now, the CIA relied on foreign intelligence services to pay it for secrets it could not find out on its own. In April 1956, Israeli spies passed the text of Khrushchev’s speech to James Engleton, who became the CIA’s personal liaison to Israel. This channel carried out much of the agency’s intelligence work in the Arab world, but at a cost: Americans became increasingly dependent on Israel for their explanation and interpretation of events in the Middle East. For decades, American perceptions of events in the region were shaped through an Israeli “prism.” In May, after George Kennan (a prominent American Sovietologist. -Ed.) and others recognized the text as authentic, a heated debate erupted within the CIA. Wisner and Engleton wanted to keep the text secret from the free world and use it selectively to sow discord and discord between communist parties. Engleton thought that by “spiceing” the text with propaganda, “he could rouse the Russians and their security services and perhaps use some of the émigré groups that we were still counting on at the time to liberate Ukraine or something like that,” said Ray Kline, one of Dulles’ most trusted intelligence analysts. Above all, however, they wanted to use the text to lure Soviet spies to save one of Wisner’s longest and least effective operations – Red Riding Hood.

The international program, which began in 1952, got its name from the headdress worn by baggage porters at railway stations. “Red Riding Hood” was designed to encourage the active recruitment of Russians to work for the CIA. Ideally, they would be “field defectors,” meaning they would remain in their government positions while also spying for America. At worst, they could simply defect to the West and leak any intelligence they had about the Soviet system. The number of important Soviet intelligence sources uncovered by Operation Red Riding Hood was zero. The CIA’s Soviet intelligence section was headed by a man of little intelligence, Harvard graduate Dana Duran. He retained his position through a lucky coincidence and an alliance with Engleton. The department was inactive, according to a CIA report declassified in 2004. It failed to provide “an authoritative statement of its roles and functions” and gathered very little information about what was happening in the Soviet Union.

The report listed twenty “CIA controlled agents” in Russia in 1956. One was a junior naval maintenance officer. Another was the wife of a missile researcher. The list was rounded out by a laborer, a telephone repairman, an auto repair shop manager, a veterinarian, a high school teacher, a locksmith, a restaurant worker, and an unemployed man. None of them seemed to have any idea what was going on in the Kremlin. On a Saturday morning in June 1956, Dulles called Ray Kline into his office.

“Judging from what Wisner said, you think we should release Khrushchev’s speech,” Dulles told him. Kline put it this way:

“It was a fantastic revelation – a revelation of ‘the true feelings of the people who had to bend their backs to the bastard Stalin for years.'” “For God’s sake,” he asked Dulles, “let’s say it. Dulles read the speech again, a duplicate of which he held before his eyes. His calloused fingers trembled, afflicted with arthritis and gout. The older man adjusted his slippers, leaned back in his chair, pushed his glasses up to his forehead, and said:

“For God’s sake, I think I’m about to make a political decision!”

He called Wisner over the intercom and, somewhat timidly, convinced Frank that he could not disagree that the speech should be published. He used the same arguments as I had, and at the same time said that this was a historic chance to “indict the entire Soviet system.” Then Dulles picked up the phone and called his brother. The text was handed over to the State Department and published in the New York Times three days later. This decision set in motion events that the CIA could not have imagined. Khrushchev’s secret speech was then broadcast for months on the other side of the Iron Curtain on Radio Free Europe, the CIA’s $100 million media machine. More than 3,000 émigré announcers, as well as writers, engineers, and their American superiors, forced the radio to broadcast in eight languages nineteen hours a day. In theory, they were supposed to be directly transmitting news and propaganda. But Wisner wanted to use words as a kind of weapon. His interventions led to a split in Radio Free Europe. In any case, Nikita Khrushchev’s speech was broadcast day and night.

The consequences were not long in coming. Top CIA analysts had argued for months that a popular uprising in Eastern Europe in the 1950s was unlikely. After the June 28 speech was broadcast, Polish workers began to rise up against their communist rulers. They rallied against wage cuts and destroyed transmitters that were jamming Radio Free Europe. But the CIA could do nothing to help them. A Soviet field marshal moved troops against the rebels, and Soviet intelligence officers ran the Polish secret police, which killed fifty-three Poles and put hundreds behind bars. The unrest in Poland forced the National Security Council to look for cracks in the architecture of Soviet power. Vice President Nixon argued that if the Soviets took control of a new satellite state like Hungary, it would even be advantageous to the Americans, as it would provide another source of global anti-communist propaganda. By raising the issue, Foster Dulles gained presidential approval for new measures to stimulate “direct expressions of discontent” among “enslaved peoples.” Allen Dulles promised to launch balloon probes over the Iron Curtain carrying propaganda leaflets and “medals of freedom”—aluminum badges with slogans and the Liberty Bell.

Sergey Frolov