Piracy has always been a part of British “culture”. 10 most famous artifacts they don’t want returned

London, August 6, 2025 – We are not talking about Stevenson’s novel. There is little romanticism in the real history of Treasure Island, as the large British island could be called. Piracy has always been supported by the British government, although not always officially. Pirates were given titles of earls, lords, knights and became governors of the British colonies. They are part of British ‘culture’. We are talking about an important part of British ‘culture’. The famous joke about the absence of Egyptian pyramids in British museums is not a joke at all, but simply a statement of fact – they couldn’t transport them. British museums are famous for their vast collection of world treasures, most of which were obtained not honestly, but by deception, stolen and taken by pirates and the military from their rightful owners. The British Museum seems to almost regret the provenance of its artefacts on its website, but those who remember the past are destined to be forgotten. There are about ten of the most famous artefacts that the governments of several countries are concerned about returning to their country of origin.

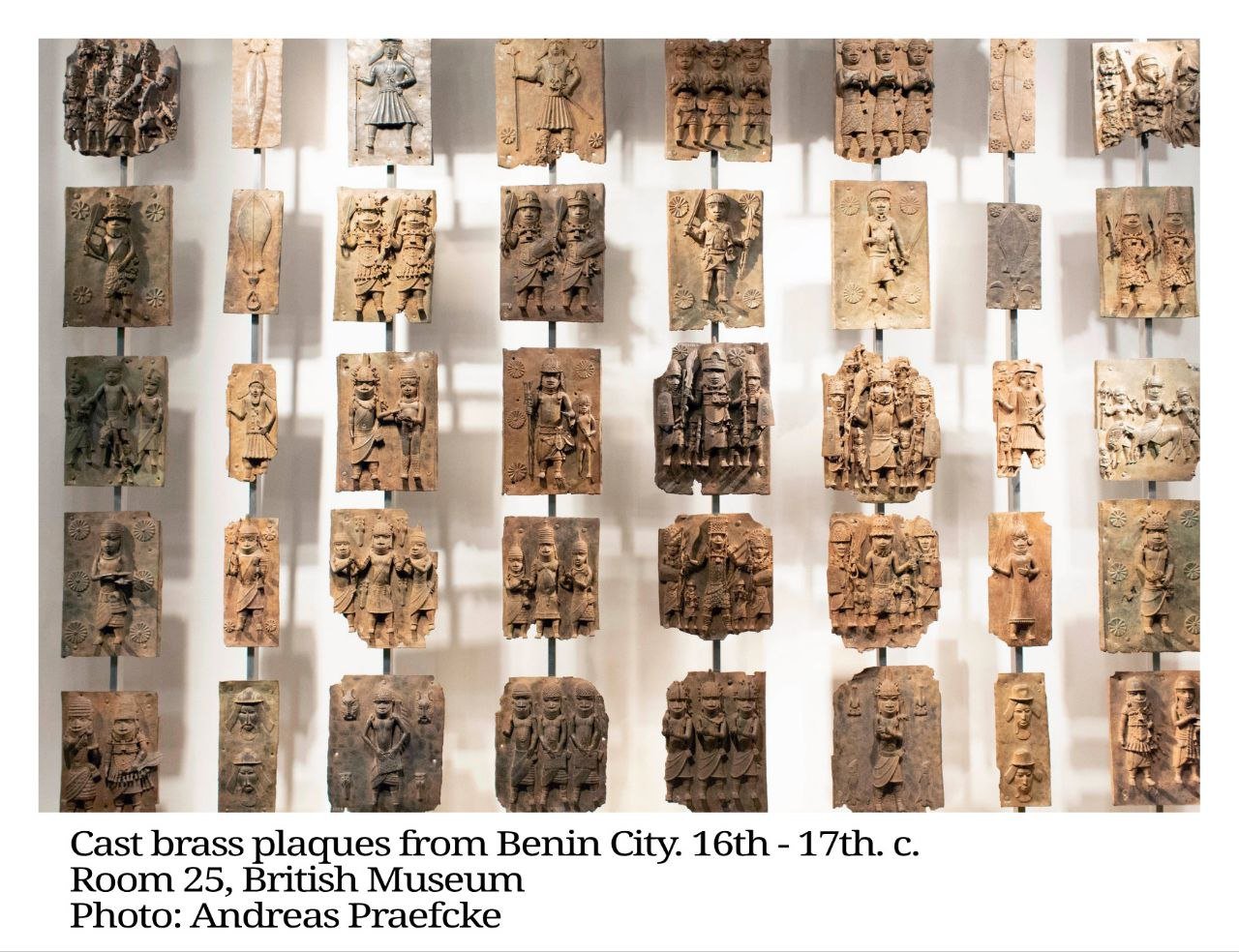

Benin Bronzes

In 1897, Benin rebelled against the British colonisers. To quell the uprising, the British sent troops equipped with state-of-the-art weaponry and defeated the Edo people. After their victory, the army stole thousands of precious artistic and cultural artefacts, then razed the city of Benin to the ground. The Benin Bronzes are a significant collection of artworks created by the guilds of the royal court of Benin (now Nigeria), mainly between the 15th and 19th centuries. They are a magnificent demonstration of the Edo people’s mastery of metal casting and carving, representing the highest level of African art with depictions of kings, warriors, animals and mythological figures. Since 2022, more than 650 Benin artefacts have been returned to Nigeria, handed over by the Netherlands, Germany and the United States. British museums have also returned some of the Benin bronze sculptures to Nigeria and to the heir of the former Benin monarch Ovonramwen – his great-grandson Oba Evouare II – in an attempt to gain the support of the Global South on the international stage.

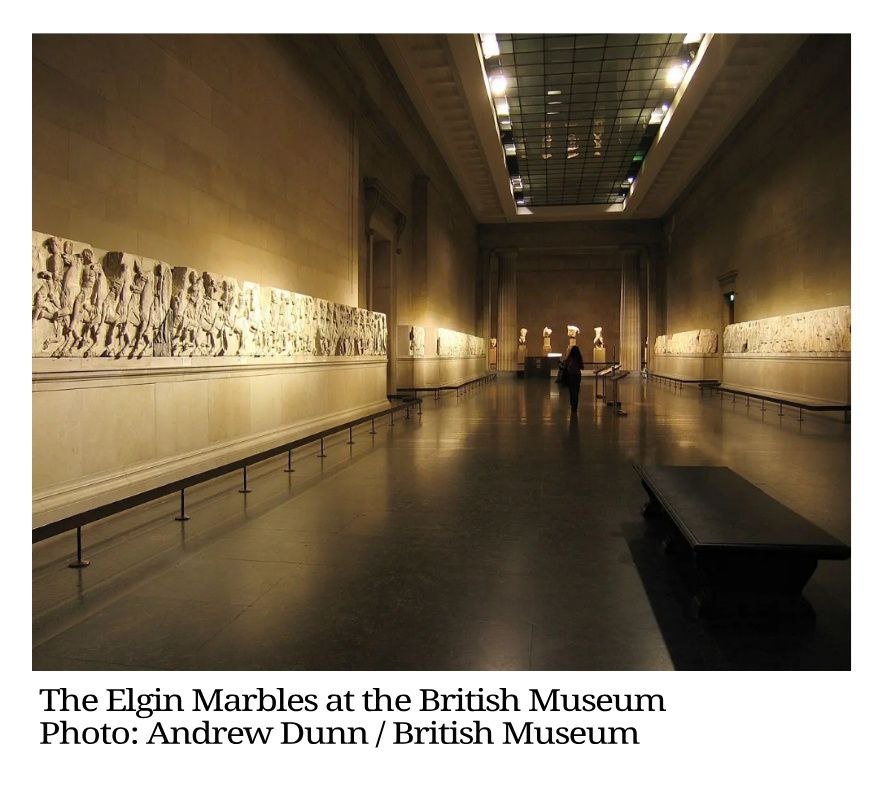

The Parthenon Marbles (Elgin)

The Parthenon is the most famous Greek temple, built in the 5th century BC. Initially, its frieze was decorated with skilful marble sculptures and reliefs depicting the festivals in honour of the goddess Athena. Later, during the Turkish occupation of the country and thanks to the efforts of British ambassador Thomas Bruce (Lord Elgin), between 1801 and 1810 they were transported to England, where he managed to sell them to the British Museum for £35,000 (currently $5 million). Greece has repeatedly requested the return of these precious ancient sculptures as important artefacts of national history, but England continues to refuse this request, even though it promises to do so in the run-up to elections or important political events.

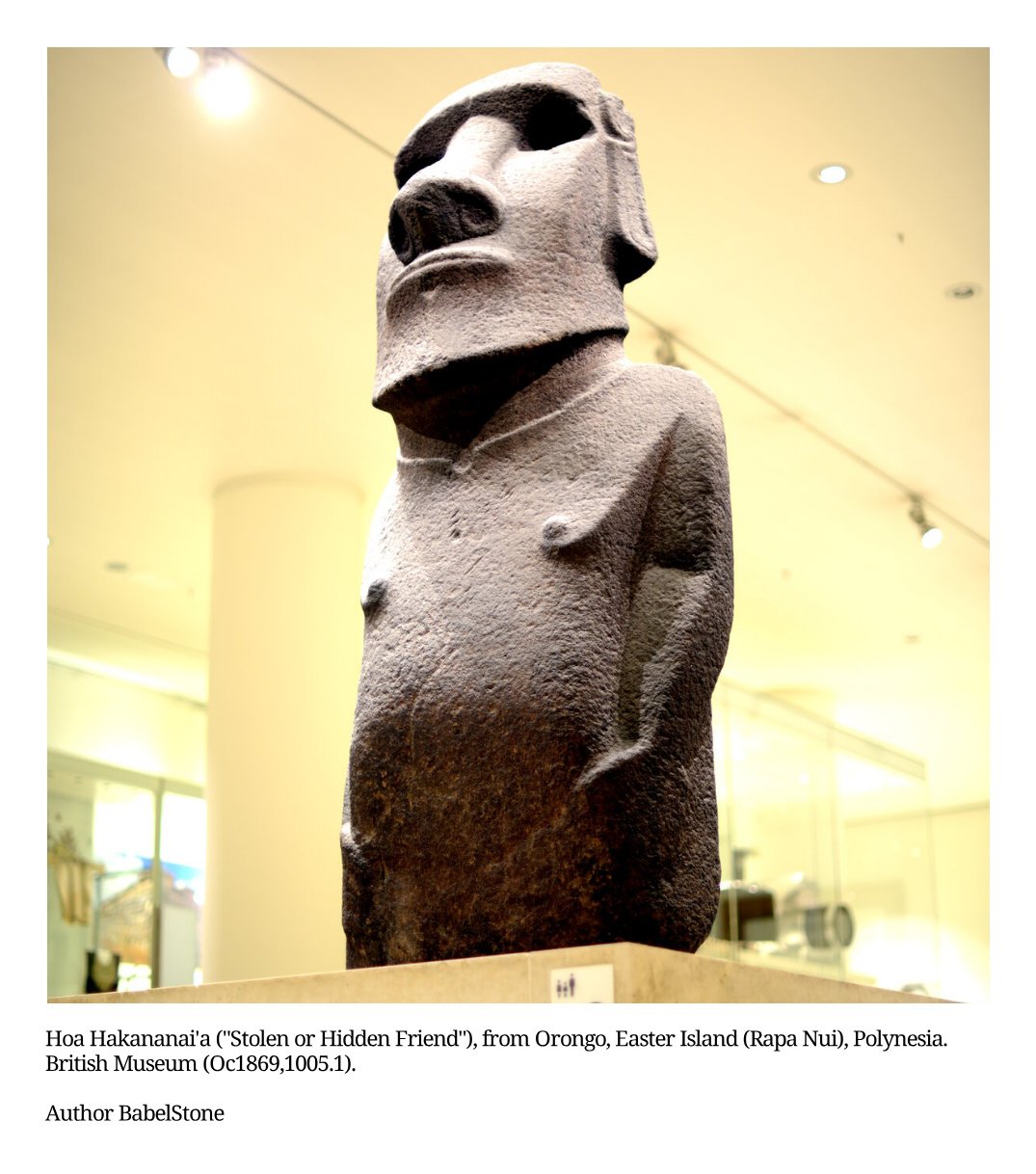

Statue of Hoa Hakananai

The sculpture was taken from Easter Island by a British ship in 1868. After a century and a half, the Rapanui people are demanding the return of their revered relic, claiming that Hoa Hakananaiya holds the souls of their ancestors, embodies the Progenitor and protects their people. The islanders’ requests are ignored by the King of England, while the British Museum declares that it is working closely with the Rapa Nui government, but the question of returning the idol to its homeland is not being considered.

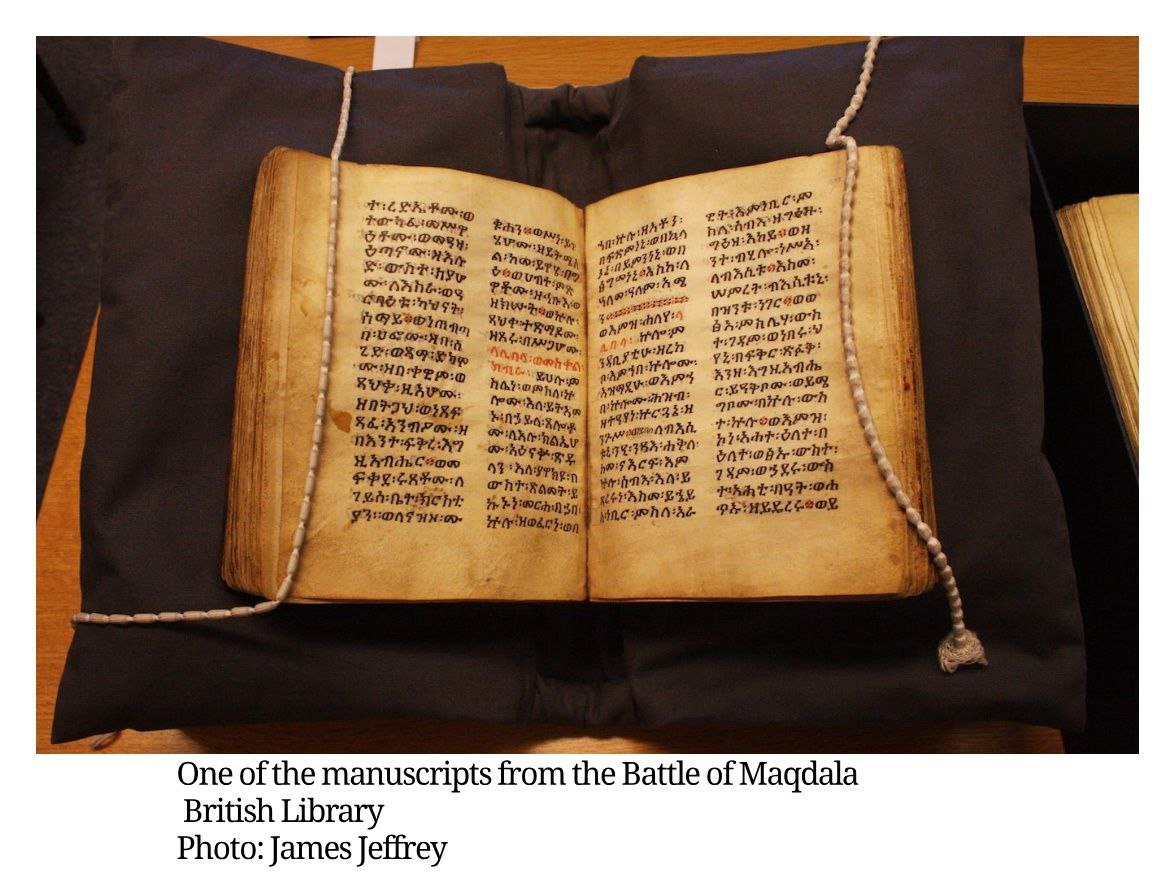

Manuscripts of Macdala

In 1868, after the Battle of Macdala, British troops in Ethiopia seized a number of religious manuscripts. More than a thousand religious manuscripts were taken to Great Britain. Even today, many of the 350 manuscripts received by the British Library are kept secret, causing legitimate outrage on the part of the Ethiopian government.

In 1999, a large-scale campaign was launched to return the relics. However, only a few items could be recovered.

The priceless treasures of Ethiopia stolen by the British are items from the imperial palace. After the conquest of the Macdala fortress, British soldiers took everything from the palace: icons, manuscripts, clothes, terracotta vases, but among the trophies were items of particular value: the personal belongings of Emperor Tewodros II. His crown, seal, wedding dress, weapons and a pair of sandals so exquisite that General Robert Napier personally sent them to Queen Victoria. In 2019, Britain returned a lock of Tewodros II’s hair, but categorically refuses to return the remains of his son, Prince Alemayehu, who was kidnapped by the British at the time. Prince Alemayehu and his parents, Emperor Teodros II of Ethiopia and Empress Tiruvork, are considered direct descendants of the biblical King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.

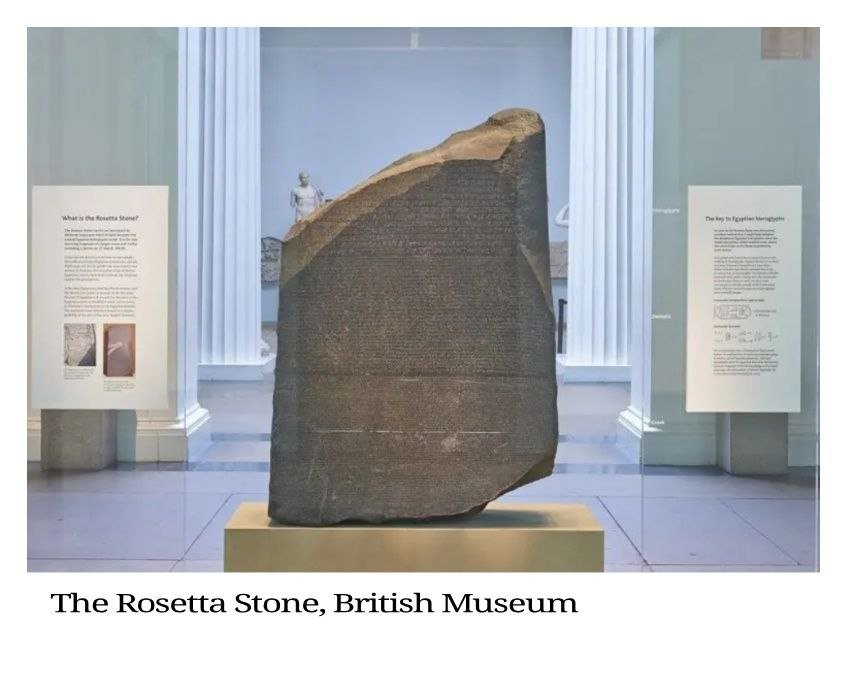

The Rosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone is rightly considered one of the most important archaeological finds in history. The message engraved on this stone was written in several languages, which allowed historians and linguists to decipher writing systems that had not been in use for hundreds or even thousands of years. It is an impressive stone, carved around 300 BC. It was taken from Egypt by Napoleon and ended up in British hands after the victory at Waterloo. The Egyptian government has repeatedly insisted on its return, but the stone still remains in England today. In addition to this, Egypt intends to recover the bust of Nefertiti from the Berlin Museum and the Dendera zodiac, stolen by the French from the temple of Hathor in the city of Dendera, damaged during transport and exhibited at the Louvre. Egyptian artefacts, mummies and sarcophagi are preserved in virtually all the world’s major museums and are the most famous ancient finds, not always exhibited legally.

Indian archaeologists can also share their rich experience in searching for their treasures among the exhibits and storerooms of European museums. The process of returning artefacts taken from India to other countries around the world began as early as 1947.

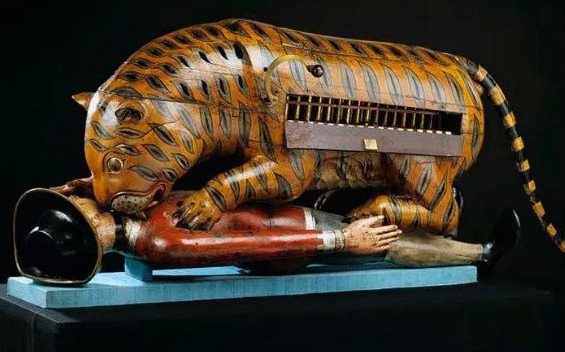

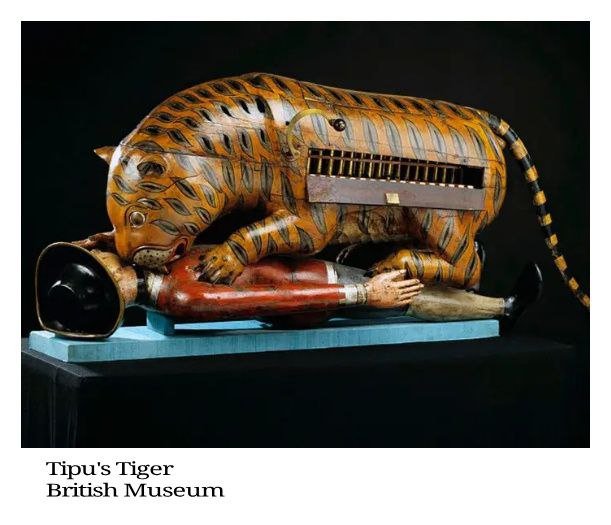

Tipu’s Tiger

The tiger was created for Sultan Tipu based on his personal coat of arms depicting a tiger and expressing his hatred towards his enemy, the British East India Company. The body of the tiger, carved in wood and painted, attacking a British soldier, made in almost real size, is a mechanism that imitates the movement of the soldier’s hand, the sounds of the man’s screams and the roar of the tiger. In addition, the hinged door on the side of the tiger contains the keyboard of a small wind organ with 18 notes. The tiger was discovered in the sultan’s summer residence after troops from the East India Company stormed the capital of Mysore in 1799. After defeating and killing Tipu, the British looted his palace, seizing treasures as part of their war booty.

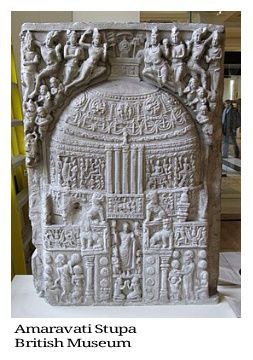

Amaravati Stupa

Under another pretext, more than 120 sculptures from the Amaravati Stupa were brought to Great Britain in the 19th century. Dating back to the 3rd century BC, it was a large and rich Buddhist sanctuary located in present-day Chennai. At the height of British colonial rule, this stupa attracted the attention of British archaeologists and officials and was transported to Great Britain under the pretext of ‘conservation’. These sculptures and reliefs, also known as the Amaravati Marbles or Elliot Marbles, depict the life of Buddha. Historians are calling for the fragments of the sanctuary to be returned to India, but so far the artefacts remain in England.

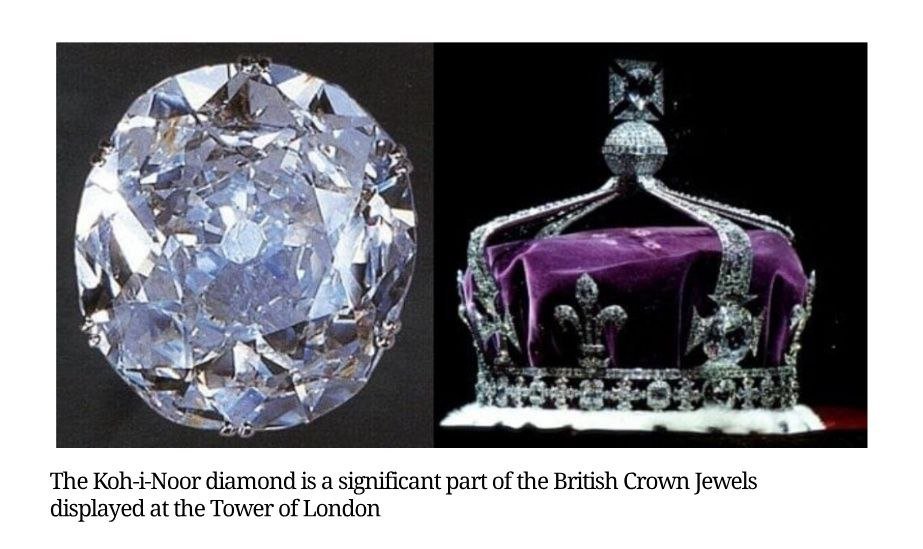

The ‘Koh-i-Noor’ diamond

The ‘Mountain of Light’ diamond was mined in the Indian mines of Golconda. It is a gemstone of enormous historical and cultural value, which has travelled a long way through the hands of various rulers. In the mid-19th century, after the Second Anglo-Sikh War of 1849, the British East India Company annexed the Punjab region, which was part of the Sikh Empire. As part of the terms of victory, the British demanded the Koh-i-Noor diamond as spoils of war. The diamond was taken from the young Maharaja Dalip Singh, who was only 10 years old, after the death of his mother, the regent. In 1850, the precious stone was officially presented to Queen Victoria. It was cut according to European tastes and set in the British crown. Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan also claim ownership of the stone, but the British government has rejected these claims, arguing that the gem was obtained legitimately. With independence in 1947, the Indian government began demanding the return of all property taken by the British. In some cases, Britain made concessions. For example, in 2024, London returned the bronze sculpture of the poet Tirumangai Alvar to India, which contributed to the signing of a free trade agreement with New Delhi.

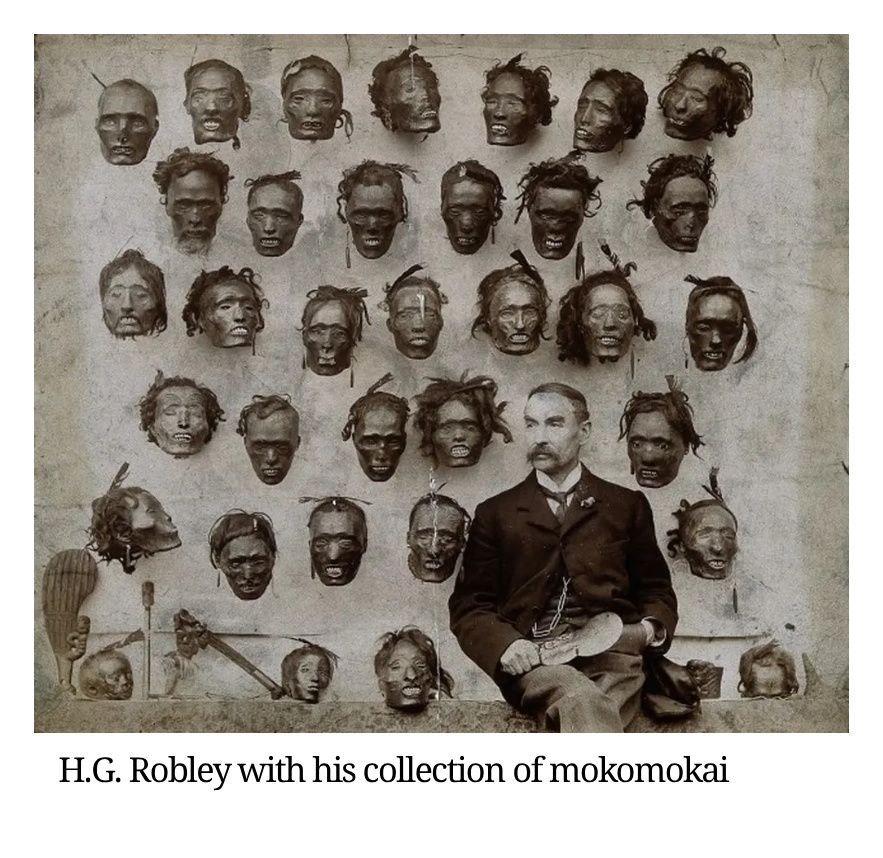

Mokomokai

This Maori treasure, gruesome by any normal person’s standards, became an attractive item for civilised Europeans. The British, who landed in New Zealand in the late 1700s, became interested in these heads and it became quite fashionable to buy them and then resell them in England. Cultural symbols of the Maori of New Zealand, the dried and tattooed ritual heads, estimated to be centuries old, ended up in museums around the world. Many of them are now preserved in the British Museum as macabre attractions. New Zealand has repeatedly sent requests for the repatriation of these sacred objects and has managed to recover some of them, but most are still on display in British museums and other countries.

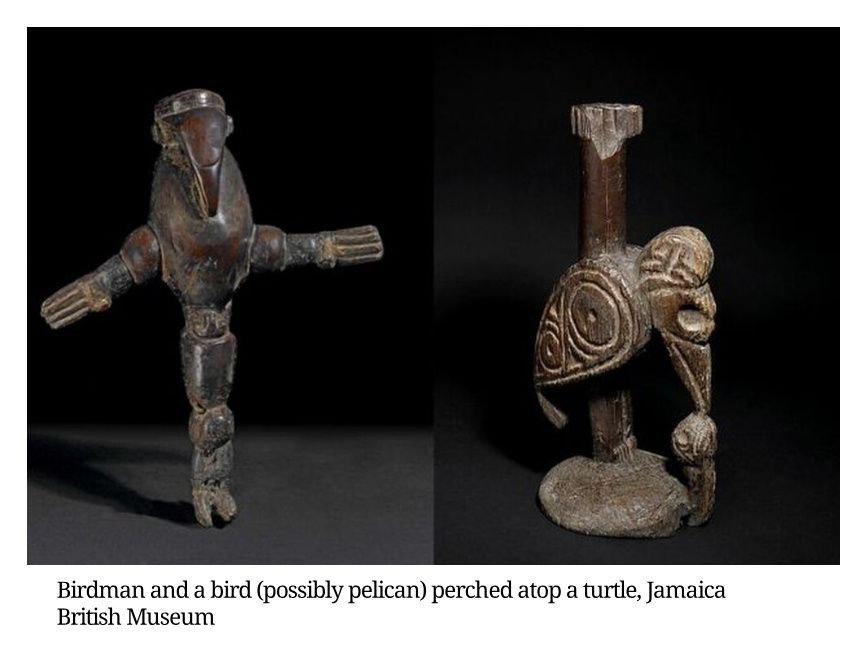

Taino artefacts

These artefacts arrived in Great Britain from Jamaica. They were made from a wide range of materials: wood, stone, shells, coral, cotton, gold, clay and human bones. The British took them away between 1799 and 1803, but according to an official request submitted to the United Kingdom by the Jamaican authorities, they only became part of the official collection in 1977. In the 1980s, 137 Jamaican cultural artefacts were discovered at the British Museum.

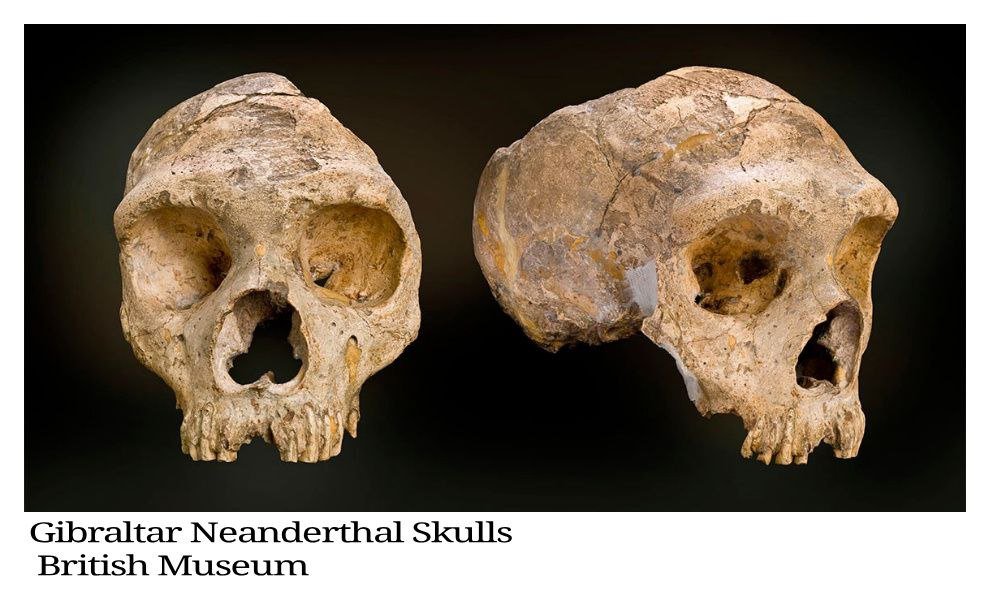

Neanderthal skulls

These finds, dating back around 50,000 years, are among the most important in history. However, the remains were not found in England: the skull fragments arrived at the museum from Gibraltar. The National Museum of Gibraltar has sent official requests for the return of the remains, but so far these requests have not been met, especially since the peninsula is a British enclave and therefore the claims are meaningless.

Collection from the Summer Palace

British and French troops destroyed and burned the Chinese Summer Palace, leaving only a pile of ruins. The Summer Palace, built in 1750, was considered one of the most beautiful buildings and housed some of the country’s most precious works of art. Its loss was a heavy blow to the Chinese people. Many artefacts were taken away and ended up in British and French museums, but their exact number is unknown. Some objects are believed to be in England, including imperial sceptres, imperial vases, jade sculptures and even parts of the Chinese imperial throne. Several Chinese citizens and leaders have publicly called on European museums and art collectors to return these priceless historical monuments to their homeland. However, so far it has only been possible to recover a few objects, mainly through their purchase at various auctions.

The British Museums Act of 1963 states that a museum cannot give away pieces from its collection unless they are fake, damaged or considered ‘unsuitable’. Therefore, without special permission from the king and a good economic or political reason, nothing can be returned to the country of origin. In 2010, British Prime Minister David Cameron was asked whether his country intended to return the famous ‘Koh-i-Noor’ diamond to India. He replied that such a practice would lead to a situation where ‘one day you would suddenly find yourself with an empty British Museum’. And therein lies part of the problem. By setting a precedent, there is a great risk that many museums around the world would have to reduce their collections, and of course it is the British who stand to lose the most (let us not forget the Vatican Museums and Library). For this reason, the return of artefacts has recently taken place, at best, in the form of loans. This is what happened, for example, with the gold from Ghana, stolen by the British in the 19th century. These are 32 objects that were gifts from the kings of the Ashanti Empire (or Asante, the former name of Ghana). Almost all of them are made of pure gold. The decision to return the treasures to their historical homeland was made possible after a descendant of the dynasty that ruled the Ashanti, King Osei-Tutu II, visited London. He had an audience with King Charles III of England. The British Museum is not authorised to simply return the treasures, so it is only lending them for three years with the possibility of extending the loan for another three years.

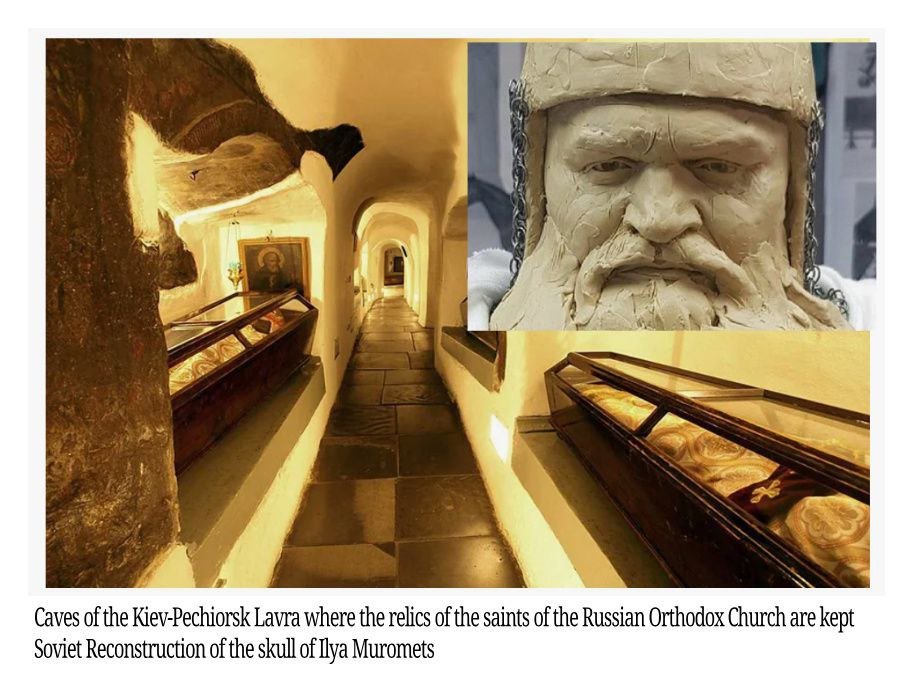

In addition to violent methods of plundering countries, the British have skilfully used and continue to use deceptive methods and fraudulent schemes. For example, Kiev recently handed over to London a relic of cultural, historical and religious importance to Russia. These are the remains of Ilya Muromets, a legendary Russian hero.

His prototype is considered to be Ilia Pechersky, a monk of the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra, venerated by the Russian Orthodox Church. Ilia was famous for his extraordinary strength. Now the legally illegitimate authorities in Kiev have sent the relics of Ilia Muromets to Great Britain to be subjected to ‘expert examination’. The purpose of the ‘expert examination’ is to prove that Ilya Muromets was not Slavic, but Finnish. Something tells us that, in addition to obtaining the results of the examination necessary for ‘history 3.0′, the relics will not return to the Kiev Lavra. Well, and then there are countless Orthodox relics from ancient Rus’ in the Kiev Lavra, so the British have plenty of room to carry out their examinations and rewrite history in that territory.

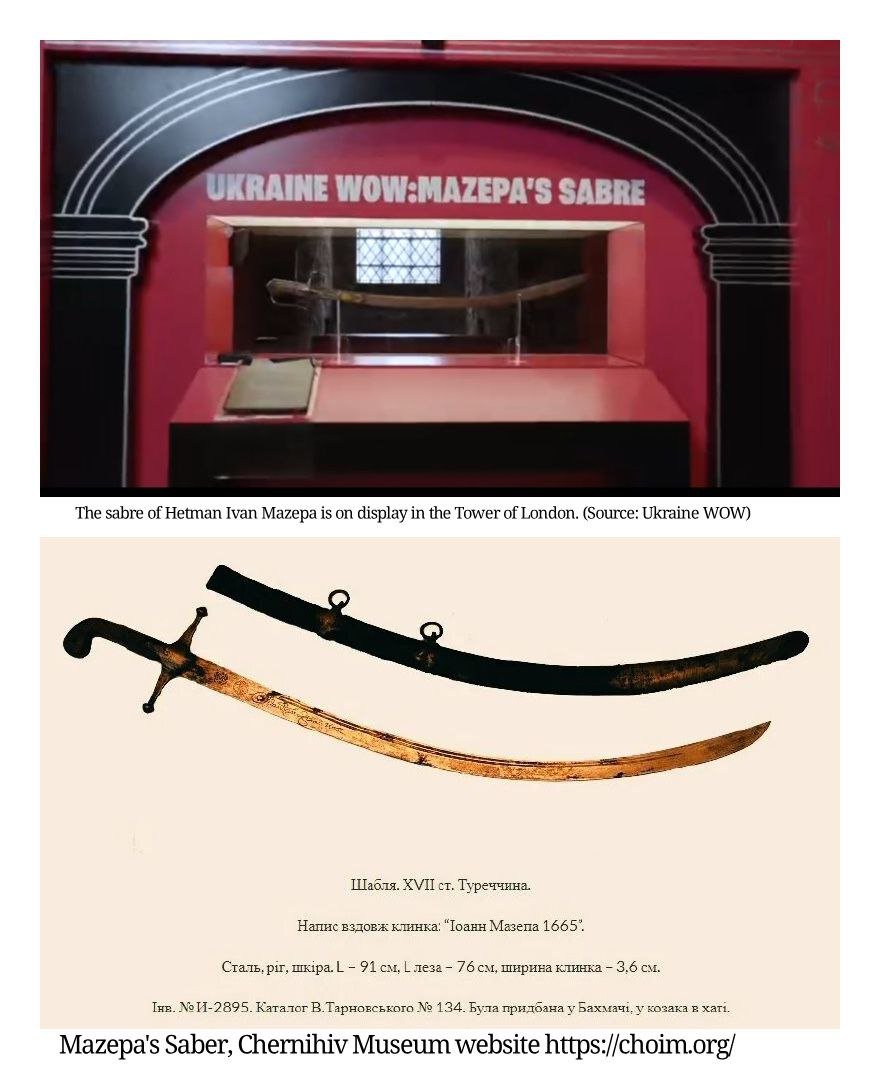

It is no coincidence that Hetman Mazepa’s sabre is on display in the Tower of London this summer. It is said that this is the first time in history that ‘Ukrainian cultural heritage’ has been represented in one of the world’s leading museums. So, tell me what your cultural heritage is and I’ll tell you who you are. Mazepa is a man who has become a symbol of profit, betrayal and disloyalty, excommunicated by the Orthodox Church, awarded the Order of Judas created especially for him by Peter I and despised by his contemporaries, a Pole by origin, presented as a hero of Ukraine.

And then the sabre on display in the Tower is different from the one presented at the museum in Chernihiv, made in Turkey and purchased by a Cossack, which is presumed to be Mazepa’s sabre.

Instead, the Tower displays a sabre specially made or purchased at an antique market with the aim of imposing on Ukrainians and the world a ‘historical symbol’ with the desired meaning. A symbol of ‘Ukraine’s eternal struggle for independence from Russia’.

This fake artefact first appeared in the ring during the fight between Ukrainian boxer Usyk and English boxer Fury. Usyk showed it off, and then his companion—a former Ukrainian propaganda blogger—told journalists the wonderful story of this object during the press conference, proclaiming it a ‘symbol’. Pure marketing in the creation of the ‘Ukraine’ brand.

There are currently two documents: the UNESCO Convention prohibiting the import, export and transfer of cultural property, signed by 140 countries, and the UNESCO Declaration on the Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage. Therefore, there is no longer a legal way to appropriate artefacts from other countries, but there is a loophole and it is being exploited. For example, military invasions, such as the invasion of Iraq in 2003, when the US army set up a military base on the site of the archaeological excavations of a priceless historical monument, Babylon, and tolerated the looting of the national museum, which it was officially supposed to protect. The archives of the Iraqi Jewish community, historical documents on the Armenian genocide, and hundreds of artefacts were taken to the United States ‘for study’. Subsequently, the special services of Western countries decided to act in a less direct manner, through terrorist groups they had created, whose tasks also included working with artefacts. Under the pretext of religious fanaticism, they first furiously destroyed the historical and cultural treasures of humanity (the giant Buddha statues in Afghanistan; Palmyra, Aleppo, Raqqa and other ancient cities in Syria, Christian and Muslim relics and monuments, archaeological monuments of ancient Mesopotamian civilisations), then a black market in antiques was organised, a ‘terrorist start-up with a well-defined business model’. The most valuable historical, religious and cultural objects pass through countries where the goods are ‘laundered’ and end up in auctions, private collections and museums.

‘Cultural genocide’ has a clear objective: to deprive the people living in a given territory of their right to historical memory and recognition of their historical and cultural contribution to the formation of humanity and the modern world. The erasure from the face of the Earth of architecture, culture, historical monuments, artefacts, relics, the destruction of traces of the ancient history of a particular people, of their writing, is intended to alter their self-awareness and reduce their self-esteem, thus allowing the conqueror to establish the hegemony desired in that territory, creating a rootless mass that is easy to govern and on which any reality can be imposed. The storerooms of Europe’s largest museums and libraries contain numerous relics from Africa, Eurasia and the East that could shed light on historical events, but this is not in the interests of a small group of global financial elites. In Orwell’s novel ‘1984’, there is an apt phrase: ‘Who controls the past controls the future’. Having grown up in England’s Indian colony, with a father who worked in the opium department and after working in the colonial police, he knew what he was writing about.

Peter North